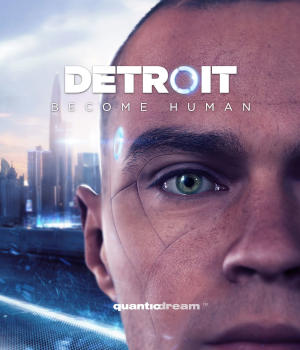

Quantic Dream’s 2018 Playstation 4 game Detroit: Become Human is a beautifully made decision based story that attempts to ask questions about the nature of man, intelligence, choice, and other important topics. One of the most important themes covered in the game is that of freedom. Detroit touches upon both freedom of the will taken narrowly as the personal faculty of choice, and upon freedom in a much broader sense as freedom for an excellence which goes beyond one’s current state in life. While Detroit does well in showing the importance of choice, it fails to integrate such free will into its broader notion of freedom and instead portrays salvation in a very Calvinistic way.

Background

Detroit: Become Human is a story which takes place in the near future (2038) in the city of Detroit, a newly revitalized city due to a company called CyberLife manufacturing androids there. The story revolves around three androids whom the player controls: A female android named Cara who is tasked with caring for a young girl named Alice, and two male androids, Markus, a messianic figure whose mission is to free other androids from their mundane servile lives, and Connor, a special android created to investigate androids who have become “deviants” by disobeying their programming, harming humans, and seeking their own independence.

Throughout the game, the player is tasked with making many choices, some small and some large that shape the course of the game for these characters and can result in wildly different plots and endings to the game. Free will and freedom more broadly understood are both key to the game mechanically, since choice is the most essential game mechanic, and thematically, since the characters, particularly those surrounding Markus, seek “freedom” from their former lives as servant androids in exchange for the ability to live their lives independently.

These two kinds of freedom align closely with the classical notions of both free choice (Lat. liberum arbitrium) and freedom (Lat. libertas). We can define free choice or free will as a faculty or power to choose between alternative goods (or apparent goods) without the choice itself being determined. Freedom, understood in a broader sense is the ability to choose not merely between some apparent goods, but the state of being able to choose the highest good. Servais Pinckaers famously called this the “freedom for excellence”.

To see these two terms more concretely in terms of human salvation, we can say that all humans, in the state of Original Sin, lack true freedom in that they are incapable of being friends with God, avoiding sin, and doing things that please God. In order to bring humans to true freedom, God offers grace to each person. Since each person has a faculty of choice, the person can choose to cooperate with God’s grace or to reject it when it is offered throughout their lives. Some may reject God’s offer altogether and never come into true friendship with God. Some, may accept God’s offer initially and then later reject him. Some might reject God’s offer but then later accept it. As Thomas Aquinas says, since human beings are free creatures, it is fitting that Gods saves them by using their freedom.

But it is man’s proper nature to have free-will. Hence in him who has the use of reason, God’s motion to justice does not take place without a movement of the free-will;

S.T I.II Q 113 a. 3

In Detroit, while free choice is explored very well, the game fails to put forth a proper view of true freedom and falls into an error very akin to the standard Calvinist view about free will and salvation.

Free Will

Being a decision game, Detroit highlights this human capacity well by using Androids. Throughout the game, the player, acting as an Android makes both small and large decisions about what to say, do, and not do which effect the character himself, and those around him. For every decision that is made, the character could have possible reasons for choosing one choice over another and yet, the character is free to choose between the alternatives. Consider just one example, that of Connor, the Android detective sent to aide Hank, a human, in investigating deviants. During one chase scene with a deviant, the deviant runs into Hank and pushes Hank off of the edge of a building. Connor has the choice to save Hank who is clinging to the edge of the building or to continue pursuit. By choosing to help Hank, Connor would be choosing to go against his programming and choose to put the well being of his partner ahead of the success of his mission. By choosing to continue pursuit, Connor would be choosing to pursue his mission at all costs. This decision provides a good example of what philosophers call libertarian free will. A libertarianly free decision is one made by reason in pursuit of a real good that is sufficiently non random nor determined. Let us suppose that Connor chooses to save Hank. In this case, his decision is not determined by either his own nature nor the circumstances. Indeed if his own nature did compel him to do anything, it would be to abandon Hank and chase after the deviant. Yet Connor, being a free agent, can choose to go beyond his own programmed nature and choose to help his partner. The decision to help Hank is one that is good, since it is ordered towards the saving of human life. It is also not merely random, since Connor has reasons to help his partner Hank.

While it is false that computers or machines as such can have free will, we can bracket that question for another time and see that Detroit does a good job of showing the reality and importance of free will to personhood. Throughout this game, especially in Markus’ storyline, the Androids will explicitly refer to “free will” as a key feature which the androids posses which makes them persons. These explicit references along with the importance of choice in the game, illustrate that free will is, as Aquinas says, part of a person’s “proper nature”.

Calvinist Salvation

While individual acts of free choice are illustrated in Detroit, the game fails to integrate this capacity into its portrayal of how androids move from their state of servitude into a state of freedom. In one scene in particular, Markus, the messianic figure whose mission is to obtain freedom for all androids, starts a march of a number of androids down a street and is able to “convert” androids whom he passes merely by an act of his own will and a slight gesture of his hands. Within minutes, Markus has the ability to “free” hundreds of androids who instantly join in his march, repeat his slogans, and then, upon his command, stand to be killed, disperse, or fight to the death. This scene mirrors the way in which God operates according to Calvinist soteriology.

On Calvinism, free will in no way plays a role in salvation. Rather, God efficaciously transforms sinners by his grace from slaves to sin, into his sons and daughters. There is no ability for the creature to cooperate with or resist his grace when it is offered and there is no ability to later on reject it either. These two ideas are often called irresistible grace, and perseverance of the saints respectively.

Both notions seems to be the present with the androids converted by Markus. At no point can they reject his offer of “freedom” and at no point do they disobey Markus or return to their old lives as slaves. This picture of freedom is contrasted with the Catholic (and Biblical) view wherein creatures do truly cooperate with God’s grace and can, once saved, continue to walk with God in their journey of transformation, or to reject God’s offer of salvation.

The Catholic View

Both Old and New Testaments are clear that God can both offer salvation to a person who will reject the offer, and also bring a person to salvation who will later fall away. Consider Israel’s journey from slavery in Egypt to salvation in the promised land. God choose Israel as his special people and brought them out of Egypt. He gave them many signs, and gave them his law. In Deuteronomy 30:15-20, God even tells Israel that they can choose between two paths, one of life, and one of destruction. As we know, some chose life and many others chose to break God’s law and fall into idolatry and other sins. Similarly in the New Testament, we often hear the New Testament writes speak of those who are “unwilling” to go along with God’s desire for salvation (Mat. 23:37), and give warnings not to fail away once saved (Heb. 10:26). Thus, the Catholic position is clearly in line with the way in which God reveals that he has worked through history to save his people. In fact, the Council of Trent even condemns as an error the Calvinist view:

If anyone shall say that man’s free will moved and aroused by God does not cooperate by assenting to God who rouses and calls, whereby it disposes and prepares itself to obtain the grace of justification, and that it cannot dissent, if it wishes, but that like something inanimate it does nothing at all and is merely in a passive state: let him be anathema.

Council of Trent Canons On Justification #4. (Denzinger 814)

Conclusion

Regrettably, the lack of free choice in android salvation is never explored in Detroit and serves as one of its main lacuna in my opinion. An improved version of the game would have been able to integrate the faculty of choice into the “salvation” or transformation of the androids from their state of servitude into their state of “freedom” rather than merely “converting” instantaneously at the whims of Markus. Perhaps they could reject his draw, or perhaps they could return to their old lives. The closest the game comes is offering Connor a choice to become a deviant or not when he encounters Markus at an android hideout. However, this one choice appears to be the exception and not the rule in the game.

Overall, Detroit is a great game and it shows the power of choice and the importance of freedom but it ultimately falls short of bringing the two distinct ideas into harmony and instead falls into an error very akin to classic Protestant soteriology of excluding free will from salvation. By reflecting on this misstep, we can come to appreciate the Catholic synthesis of freedom and free will in God’s plan to save humanity from sin.